an opportunity to integrate care in a sustainable way

We live in a time of unprecedented humanitarian emergencies, many of which are both created and exacerbated by armed conflict. Communities displaced by conflict, more than 80 million people worldwide, are often forced to leave their homes in extremely difficult conditions and live without access to the most basic essentials for everyday life.

Having already faced stressful events in their country of origin (violence and loss), refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) may face additional stressors such as poverty, discrimination, overpopulation, disconnection from their previous sources of social support, and food and resource insecurity. In addition to these challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in widespread anxiety, fear and hardship. As a result, these communities face adversity on multiple fronts, which increases their risk of developing mental health problems.

Almost everyone affected by humanitarian emergencies experiences psychological distress, with one in five likely to suffer from a mental disorder such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

An influx of refugees requiring psychological and psychosocial support

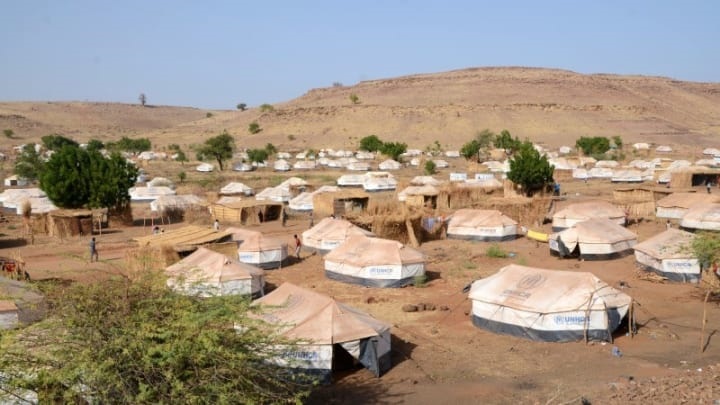

In early November 2020, Gedaref, a state in eastern Sudan, witnessed an influx of tens of thousands of refugees fleeing the Tigray conflict in Ethiopia. Already housing 1.2 million refugees – the largest refugee population in the region – Sudan’s health system was quickly overwhelmed. Pieter Ventevogel, senior manager of mental health and psychosocial support at UNHCR, who visited the refugee camps six months after the onset of the crisis, recalls the “high burden of grief, loss, trauma and depression. resolved which was visible during discussions with the refugees ”. Protection officers explained how prevalent untreated gender-based violence was among refugee women, and staff working in child-friendly spaces reported how children represented violence and corpses in their drawings.

Assefa, a refugee who fled Tigray with his family, recounted how his family struggled to support his daughter who suffered from a mental health problem: “Almaz is my daughter. The situation in Tigray affected her mental health and she began to behave in a violent and erratic manner. We didn’t know how to handle things, so we used to tie him up. I tied her up in our car on our way here, tied her up in the tent we were given, and later to our house. There was no health center available at the time, nor any medication for its treatment. “

In Sudan, resources for mental health are limited: there is an absence of psychiatric nurses, a shortage of clinical psychologists and only two certified child psychiatrists available in the country. The influx of refugees has strained existing resources. Two mental hospitals in the country’s capital, Khartoum, and 17 outpatient mental health facilities serve more than 40 million people across Sudan. Only a handful of Sudan’s 18 states have a trained psychiatrist.

Include mental health and psychosocial support in the humanitarian response

Historically, humanitarian assistance programs have often overlooked the need to integrate mental health and psychosocial support services into response efforts, despite overwhelming evidence of increased vulnerability of displaced communities to mental health issues. To address this issue in Sudan, UNHCR and WHO are working with the government on an approach to mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) that includes three core elements: engagement of community leaders; integrating support into the wider health system; and ensure the quality of the services provided through supportive supervision.

Engage community leaders

In Sudan, a key strategy was to involve community “gatekeepers” – religious leaders, respected community leaders and traditional healers – to ensure community uptake and use of services. Through this approach, community members are helped to rebuild disrupted social networks and support structures and find their own solutions to their problems. Dr Brian Ogallo, WHO Technical Officer for Mental Health, explains: “Sudan is a very religious country, so religious leaders and traditional healers are very influential in the communities where we work. They are keepers; their involvement and inclusion are therefore crucial for the success of any intervention. In our most recent MHPSS training of trainers, we involved a traditional birth attendant, who is well respected in her community. She is now equipped to train other community members in basic psychological first aid. But more importantly, it combats common misconceptions about mental illness, thereby reducing mental health stigma and encouraging uptake of services.

Integration of mental health into the primary care system

While community members can be trained in basic psychological first aid (PFA), there is also a need for services for people requiring higher levels of care, including those with severe mental health problems. In Sudan, people with serious illnesses currently rely on two tertiary level hospitals located in the capital. The program therefore works with the Ministry of Health to integrate mental health into primary health centers and to strengthen referral pathways. A key activity in support of this goal has been to organize MHPSS integration workshops for health providers at all three levels of the health system. More than 20 psychologists from the ministry participated in a training of trainers workshop on topics related to mental health, including: PFA; Problem Management Plus (PM +), an evolving psychological intervention for people affected by adversity; and the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program Humanitarian Response Guide (mhGAP-HIG), a guide to providing basic mental health care in general health and primary care settings. These master trainers will in turn train other health workers in primary and secondary health centers, thereby accelerating the availability of mental health services at all levels of the health system. This training of trainers approach for capacity building allows the training of a cadre of health providers trained in SMSPS in health facilities, thus ensuring the continuity of services after the end of the project. In Gedaref, UNHCR trained 22 health workers who were either involved in humanitarian outreach or from the state health ministry, using the mhGAP methodology and materials developed by WHO and its partners.

Provide quality services through supportive supervision

The integration of mental health services into health systems is supported by ongoing supervision after training. Dr Fatima Hassan Mohamed, Sudanese senior resident in psychiatry, was deployed by the non-governmental organization ALIGHT, with funding from UNHCR, to a refugee camp in Gedaref to supervise trained health workers and ensure quality control . Fatima said, “As we build a quality mental health service delivery system at the community level and in refugee camps, through trained and supervised health providers, I have seen a considerable change in people’s perceptions of mental health itself. They see how mental health services are offered alongside other health services. They observe how mental illness, like any other health problem, is treatable. As I supervise skilled health providers, I realize that I am not only delivering quality services, I am in fact part of an effort to transform the way mental health is viewed in communities across the country. across Sudan.

Almaz, who arrived in Gedaref chained to her family’s car, is an example of how relatively modest resources and investments in mental health can deliver significant and tangible results. Trained service providers visited her home every three days and supported her recovery with a combination of medication, counseling and psychoeducation, all provided at the community level. They involved family members in her treatment process and demonstrated how vital their support was to her recovery. Her recovery demonstrated to the community, both refugees and members of the host community, that mental illness can be treated and that everyone deserves access to mental health services.

The approach in Sudan shows how strengthening national mental health systems is possible through responses provided in humanitarian contexts. Using a “health systems approach”, the program builds health care capacity in Sudan and enables its public health system to function independently from humanitarian initiatives. Despite systemic challenges, such as barriers to drug supply and high rates of staff turnover, efforts in Sudan have strengthened the capacity of health staff and community mechanisms to provide mental health and psychosocial support for children. quality, which in turn contributes to more resilient communities.

Comments are closed.